Qantas pilot Captain David Summergreene has spent a quarter of a century flying passenger jets around the world. But his epiphany came while he was sitting at his desk and staring at rows of numbers on a computer screen that illustrated how the Australian national carrier was using jet fuel. “For the first time, I was able to self-service as a pilot to look at some of the most interesting metrics to me, rather than having to go to an analyst and ask, ‘Can I have this information, please?’” he says. “I was just overwhelmed by this; I was like a kid in the candy shop.”

But then another thought hit him. He could see the information only because his managers had asked him to help the airline save fuel. “It dawned on me: ‘But hang on a second, we’re not giving this data to the pilots, the people that can make the biggest difference with it.’ It was almost like a football coach working out a game plan, but not communicating that game plan with the players. Unless you got that data out in the hands of the pilots, you were not going to be able to affect the change that you wanted to make.”

The flash of insight took place in 2016, and Summergreene has spent the past six years working with GE Digital, the company that developed the original fuel usage database, to build a pioneering app called FlightPulse that pilots can bring to the cockpit. The software is designed to provide insights derived from flight data to pilots, kind of like a health app tracking steps and calories. The latest version of the software is intended to give pilots data that allows them to evaluate each flight before and after landing, compare their performance to that of their peers and airline benchmarks, and plan for future flights.

Today, more than 2,000 Qantas Group pilots across six airlines are using FlightPulse, and the operator calculated that the app has helped enable a 15% increase in the adoption of fuel savings procedures and avoided 5.7 million kilograms (6,300 tons) of carbon emissions in the first year of use. In March 2022, the Qantas Group highlighted the FlightPulse app in its Climate Action Plan as a means to help reduce net carbon emissions by 25% by 2030 and help increase its fuel efficiency by 1.5% per year to the end of the decade.

“When this started, I was like a dog with a bone,” Summergreene laughs. “I was not going to let go. I had to convince people of the power of what this data was and what it would mean for the industry. And to be honest, at the time I probably didn’t realize the power this product could wield. Now I’m excited to see where that goes.”

FlightPulse and other software GE Digital has built is helping chart the course for “the perfect flight,” an effort designed to help enable airlines to operate at their peak efficiency and reduce their carbon emissions. The industry contributes about 2.1% of all CO2 emissions tied to human activity, and many airlines are seeking to reach their “net zero” emissions goal by 2050. Using fuel smartly and being able to measure the savings is an important part of that journey.

“I’ve been very fortunate in my time to do a lot of travel, and I want future generations to be able to enjoy that as well,” Summergreene says. “It’s our responsibility to be able to step up and make sure that air travel is not only efficient, but it is sustainable.”

Time to run

Sustainability is a topic that also occupies Andrew Coleman. He runs GE Digital’s aviation software business, the unit that developed FlightPulse with Qantas. But for Coleman, it’s bigger than just one app. He and his team have developed a suite of software applications that airlines around the world are using to help make their operations more efficient.

Coleman says he’s working with a sense of urgency. While renewables have become the fastest-growing sector of the energy industry, and EVs are the future of the car industry, aerospace has been difficult to decarbonize. Batteries are heavy, making hybrid-electric and electric flight possibly decades away. And while airlines have started using biofuels, also known as sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), the infrastructure that would make SAF widespread is also still in development.

But Coleman points out that software solutions that can help airlines improve their impact on the environment are already here. “The industry is racing to reduce emissions,” he says. “The only way to get the kind of acceleration we need to hit that goal is to put data to work that is already available in maintenance, operations and flight itself.”

30,000-data-point view

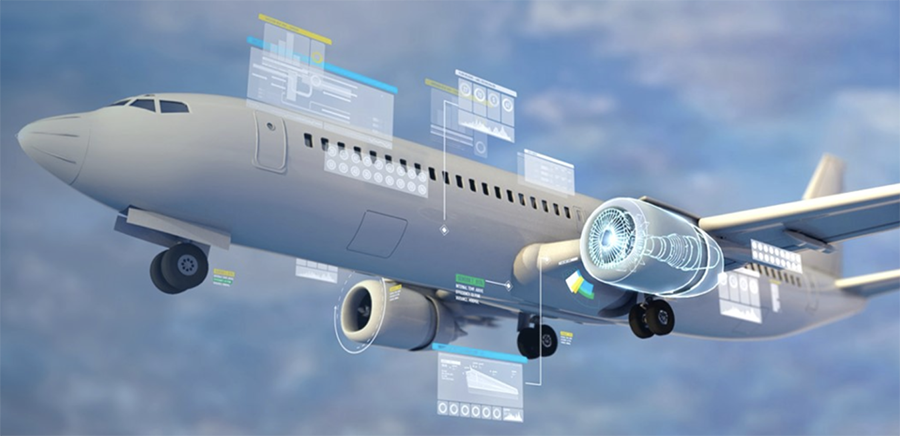

Coleman says that a modern aircraft like a Boeing 787 can collect as many as 30,000 data points, as compared with about 80 not so long ago. Sensors can track engine performance, landing-gear stress, hydraulic pressure, all the way down to the temperature of the coffeepot and the number of times the toilet was flushed. “The level of analysis and clarity we can get with our software is like going from a handful of Polaroid snapshots per flight to a high-definition movie,” he says. “You can see every little detail.”

Some of these details can be simple, but they add up. Tracking actions like whether pilots are using just one engine to taxi at the airport and whether they plugged the plane into the airport’s power system at the gate instead of keeping the plane’s auxiliary power unit running can help reduce the amount of fuel a plane burns on a trip. They can also leverage human psychology by allowing pilots to see how they’ve been flying and compare their performance with that of colleagues working the same routes. “No one wants to be in the bottom percentile,” Coleman says. “Pilots self-correct. Nobody has to send them an email and say, ‘You’re not doing it right.’”

Take it to the bank

The potential to drive better outcomes with software is enormous, says Scott Reese, GE Digital’s new CEO. “From insights about maintenance to fuel benchmarking to airspace efficiency and beyond, software can help achieve a more perfect flight sooner than many think is possible,” he says.

Reese points to GE algorithms in place today that, for example, help carriers manage aircraft fleets, plan routes and maintain jets. Coleman agrees. “If the software detects three hard landings in a short period of time, it might suggest you check the landing gear,” he says. “Or if you fly two planes to Atlanta three times a day, it can see that one has a very different CO2 profile. Maybe you carried too much fuel and all that extra weight made your fuel consumption and emissions go up? It can be a million things, and we can help you find out what it is.”

Software also allows owners to track the condition of their jets. Coleman says that of the approximately 30,000 aircraft in service, a quarter are being monitored by GE software. And there’s more. More than half the planes in service today are leased by airlines from banks, much like how many drivers lease their car. GE software allows the lessor to monitor how the plane is being operated. It also creates a digital record that helps shrink from months to just weeks the time it takes to more safely transfer the jet when the lease ends from one airline to another. “We recently completed the first-ever fully digital transition of an airplane, no pen and paper required,” Coleman says. “When a multi-year contract ends, the owner wants the new operator to be able to get that plane into profitable operation as quickly as possible.”

Ones and zeros

Just like cars, planes were for many decades mechanical machines controlled by levers, pulleys and wires. Even the first flight recorders, introduced in the second half of the last century, were primarily voice-recording devices storing conversations in the cockpit and analog instrument readings.

When computers entered aviation some 50 years ago, the industry settled on digital standards it still uses today. “Think of it as the internet protocol, but for the airplane,” says Andy Rector, vice president of digital engineering at GE Digital Aviation. “Airplanes fly a long time, and it takes decades to change these types of things.” This legacy helps illustrate some of the hurdles aviation software programmers must scale. “The flight data is literally flowing ones and zeros in a very old format that was defined in the 1970s,” Rector says. The Boeing 787 Dreamliner, in service since 2011, was the first plane to get an upgrade.

Rector says GE’s success in the field owes a lot to an early focus on solving the right problems and on close relationships with customers. “Our approach was: Do whatever we can for the customer, but do it in a scalable way,” Rector says. “Build Lego blocks that I can then reconfigure for airline A and airline B. And I can serve them uniquely and meet their needs and deliver them value. But do it in a cost-effective way.”

The math engine that could

The first blocks the team built created a platform that converts those ones and zeros to engineering units — for example, “10011” is 36,000 feet. “Anyone that works with data knows 90% of effort is cleaning up the data and getting it into a consumable format,” Rector says. “We have worked for decades to master how to clean that data and convert it into consumable formats. And then we’ve created a math engine that can process all of those converted numbers from different types of planes.”

All kinds of math are in play, from tracking fuel usage, helping with fleet scheduling and sending the right plane to the right airport to maintenance and a plane’s health record. “We built this scalable platform, we built the right abstractions in there where we can run the same exact stuff,” Rector says. “We started with safety, but today we’re doing the same thing for sustainability.”

Rocket problem

How? “It’s the classic rocket problem,” Rector says. “I never want to run out of fuel, so I’m going to put so much extra fuel on this aircraft that I don’t have to worry about that. But if you do that, you then burn more fuel to carry more fuel. The only way you can find that local optimal perspective is to have a ton of data so you can factor for all the different things for that particular flight to tell you where that little sweet spot is.”

Rector and his colleagues know which sweet spots to look for because of their close relationship with airlines. “To know how to improve, you first have to know how you’re doing today,” says Joel Klooster, vice president for product management and strategy at GE Digital Aviation. He says that GE software can combine the rich data from the plane with information from the headquarters that offers insights into how the airline operates, and external sources like the weather a plane flew through. The result can be an easy-to-understand snapshot of how the airline is doing today versus the industry. “What’s really impactful about this is you make it a data-driven discussion,” Klooster says. “You’re taking the emotion out of it, you’re taking the hypotheticals out of it, and you can really understand what are the very specific things that are stopping us from being more efficient today. Once you understand that, there’s millions of opportunities every day to keep getting better.”

Common goals

Which brings us back to Qantas. Jonathan Morrell and Luke Bowman were two GE Digital product managers who worked with Summergreene to help make FlightPulse a reality. “Dave came in said, ‘You guys have all this data. Why are you not giving it to the folks out in the field?’” Bowman recalls.

Before long, Morrell and Bowman interviewed dozens of pilots to make Summergreene’s epiphany a reality. “We put our designs in front of pilots and they were like, “I don’t know what this is,” Morrell recalls. “We had a number of these moments where we had to go back to the drawing board and basically figure out what a pilot needs. A pilot is not a data scientist. A pilot is not an analyst. A management pilot is not the same as a line pilot. Our apps have been built from the ground up on that level of research and level of customer engagement.”

Morrell says GE has been able to cultivate this sense of collaboration by having a long history of helping the industry fly safely. “We have staked our reputation on our level of collaboration with the airlines and the trust that the airlines have with us,” he says. “Without having that underlying trust that we’ve built over the years, it wouldn’t be possible to work toward this goal together.”

With GE planning to go forward as three independent companies focusing on aviation, energy and healthcare, GE Digital, which makes software for aviation, manufacturing, power and other industries, will become part of the new energy business. Coleman says that the world’s focus on sustainability helps illustrate why. “The reality is that manufacturing things is different than producing electricity, which is different than managing the grid, which is different than aviation,” he says. “But there’s a common CO2 footprint around all these things that’s got to go down,” Coleman says.

Says GE Digital CEO Reese: “We believe sustainability is the future of flight. Software developed with and for our customers — leveraging data we already have at our fingertips — is the unique accelerator to help make it happen.”