In early March, Kathy Armijo Etre was managing community outreach as vice president of mission for New Mexico’s oldest hospital, the Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center in Santa Fe. The hospital serves as the northcentral New Mexico hub hospital and is assisting with the statewide response to the COVID-19 outbreak amongst Native American populations. In her regular role, Etre set up programs to serve the area’s homeless and care for other vulnerable patients. But when the coronavirus pandemic hit the state, the entire hospital staff had to prioritize one thing: getting enough personal protective equipment (PPE) to care for the coming wave of COVID-19 patients.

Etre knew she had to move fast. Companies, innovators and garage tinkerers had to come up with quick and clever ways to make PPE in a pinch and help keep first responders safe. She went through her list of contacts and reached out to Sarah Boisvert. A former high-tech manufacturing executive, Boisvert is now active in New Mexico’s “maker” movement and runs digital fabrication labs for students in Santa Fe.

Boisvert listened and put Etre in touch with Sherry Lassiter, who runs the Fab Foundation, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) spinoff nonprofit that promotes digital fabrication technology and education. GE’s philanthropic arm, the GE Foundation, partners with the Fab Foundation to introduce Boston-area students to high-tech equipment and education through mobile STEM labs. Lassiter added the Christus St. Vincent staff to her growing list of organizations with critical PPE needs.

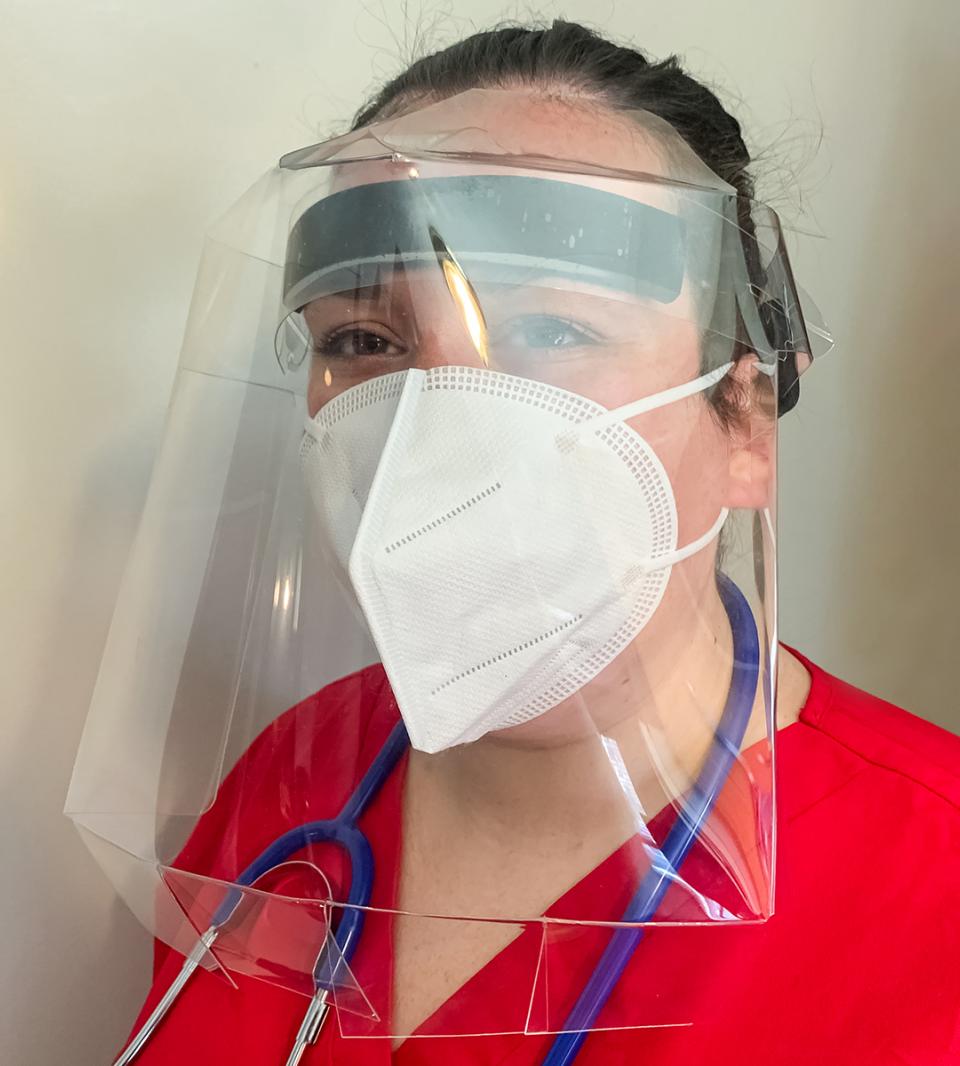

Lassiter was working already with MIT professor Martin Culpepper and his students as they were designing and producing protective face shields to get them to communities in need. Dubbed the school’s “maker czar,” Culpepper designed a flat, clear piece of plastic perforated so that it is easily folded into a shield that wraps around the wearer’s face and helps better protect them from exposure than normal face shields. But while Culpepper’s design could be 3D-printed or milled, it was a slow process, only a few hundred could be produced in a day.

Culpepper connected his shield design with a plastics die cut manufacturer that could cut them and churn them out by the tens of thousands. The MIT face shields can be cleaned and reused and have freed up other protective equipment for use by Christus St. Vincent staff.

The results of the collaboration materialized in early May. Thanks to funds from the GE Foundation, the Fab Foundation donated 1,000 plastic face shields to Etre’s hospital and another 1,000 to a hospital in Tuba City, Arizona. MIT’s protective equipment allowed the Christus St. Vincent team to stockpile gear just as the coronavirus surged within the region’s Native American pueblos and reservations. “Our highest priority was to assure that our clinical team was protected from exposure. The lack of appropriate PPE caused a lot of worries,” says Etre. “Knowing that we had to do it ourselves, the MIT face shields for us were such a godsend.”

The donation came at a pivotal moment. By mid-May, the sprawling Navajo nation saw higher rates of infection than New York and New Jersey. In addition to extreme poverty, many Navajos have limited access to running water for hand-washing and often live with many generations under one roof, making social distancing difficult. Those roofs are also often far from one another, making travel for essential supplies yet another vector for transmission.

Compounding the challenges for healthcare workers treating these populations were cultural and language barriers. “Caring for Native American patients is a completely different world,” Etre says. The Pueblos live in rural area and the Navajo Nation Reservation spans 27,000 square miles across three states.

Etre recalls her colleagues struggling to set up a video call with the family of a man dying of COVID-19. His relatives had to travel to a community center for internet access and coordinate the timing for what might be the man’s last chance to see family. It took two weeks to locate the relatives of another patient because his family members had been hospitalized at various hospitals throughout New Mexico.

Lassiter sees the Fab Foundation partnership with MIT, the GE Foundation and the hospitals as a prototype for linking up the maker movement with communities in need. The MIT group plans to ramp up face shield production to 50,000 per day. Fab Foundation's network of fab labs is also working out how to make the material for N95 masks, Lassiter says. The nonprofit could then supply Native communities with the machines, material and training to make and sell the masks, producing a product in great demand and jobs at the same time.

“We’ve had partnerships with humanitarian organizations before, but usually we provide them with digital fabrication equipment and training,” Lassiter says. “This is the first time we’ve done anything like this. It’s amazing, fascinating, overwhelming and incredibly exciting in terms of the way it points to the future.”